The Royal Brompton in Chelsea is one of three hospitals in London with the facilities and staff to treat children with heart defects. An estimated 5,500 to 6,300 babies are born with congenital heart disease in the UK each year, all of whom require specialised care. Some will need many operations throughout their life.

On Friday, the Guardian will be live blogging from the Brompton, where congenital heart disease services are under threat of closure. Advocates of the change say concentrating services in fewer locations makes for better care; the hospital and its supporters say it is the best at what it does in the country. The Brompton treats children with heart and lung diseases aged from just days old to 16 years. It has a paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) for children after surgery with at least one dedicated nurse per child, the Rose ward for 30 inpatients, and four beds in a high-dependency care unit (HCU).

- Morning routines: the ward-around meeting, and breakfast on the fly for the nurses

Doctors, consultants and nurses tour the paediatrics department in the morning ward-around. It is a crucial opportunity to discuss the various cases and what to expect for the day ahead.

Young patients

Kawaljit Kaur spends all day, every day, at the bedside of her first and only child, Ekam, who is five months and 19 days old, she says, and was born with a hole in his heart. “I play with him. He holds my hand. We talk to each other and he gives me a smile,” she says. Ekam, sleeping flat on his back with his face hidden by tubes, flails his limbs in the air. “He is very lively,” says a nurse.

After work, Kaur’s husband joins her before they go home for the night. And in the morning she is back. “On Saturday and Sunday we are both sitting here, watching what he is doing,” she says.

- Autumn Russell with her mother Keri

Fifteen-month-old Autumn Russell from Essex was transferred to the Brompton for specialist treatment for a case of empyema, a bacterial infection that develops in the slim space between the outside of the lungs and the inside of the chest cavity.

Time may pass slowly on the ward in the paediatric heart and lung unit, but for children like Ekam and their parents, the hospital becomes part of their life – a second home and a place of hope. Ekam’s veins are still too narrow for the heart operation he needs, so he has a succession of stents fitted – tubes inserted into blood vessels to increase the flow.

Marciee Barnes-Palmer has respiratory problems as well as a congenital heart defect. She underwent a microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy procedure to look at her upper airways, and doctors will need to close the hole in her heart.

- Dr Jana Kossaibati uses a torch to locate a vein to insert a cannula in Marciee’s hand. Nurse Patience Makuyana holds Marciee’s brother Freddie

Consultant clinical psychologist Michele Puckey supports the families, patients older than about three, and their siblings. “Brothers and sisters have to be reassured that they have not caused it,” she says. “And the child in hospital must not be treated like a princess – or they will not fit in at school when they get back to real life.”

Between four and seven they have this extreme feeling of being in control of everything around them. Children feel responsible for parents arguing and separation

– Michele Puckey

Staff need support too and Puckey herself is not immune. “I remember once a boy going down to theatre in the same pyjamas as my son and I just caught my breath.”

- Rachel, the mother of Ellarna, speaking with Dr Cathy O’Donoghue

Ellarna is 32 weeks old and has had a catheter procedure today to close a hole in her aorta. Anaesthetic and critical care consultant Cathy O’Donoghue visits to discuss the operation.

For premature babies, the Brompton is the only centre in the UK using this method as an alternative to surgery.

Teenage patients

Ellie Bartram, 16, has been coming to the Brompton since she was diagnosed at four months old with cystic fibrosis, a lifelong condition that clogs up the lungs with mucus. She is admitted for two weeks every three months for an intravenous course of antibiotics.

- Ellie Bartram in her school class in the paediatric ward, and undergoing lung treatment

There is a schoolroom on the ward, where Ellie has lessons. The teaching is good – she and her mum Sarah credit a tutor at the Brompton for getting Ellie through her French GCSE with a C grade.

I can’t run around. I can’t go out much or go out with friends often. But my friends come and buy me McDonald’s because it’s my favourite thing

– Ellie Bartram

In her solitary room, where visitors must wear aprons and gloves for fear of giving her an infection, she talks to her friends via FaceTime. “I’m used to it,” she says. She doesn’t like being different, but she is matter of fact about life at home in Romford, Essex.

- Riley Jenkins , 13, grimaces in pain as his mother helps him put on a shirt. Riley had cardiac surgery three days ago

Riley Jenkins, 13, is feeling very sick. He can’t eat the meatballs for lunch. His mother Sally rubs his back to try to make him feel better. It is the after-effects of the anaesthetic and the operation to replace a calcified heart valve that was inserted in his chest when he was just seven months old. “He’s been coming for a checkup once a year since he was a day old,” says his mother, Sally.

Riley was born with a back-to-front heart. “He loves Scouts and being on his computer but he’s been too tired to do a lot of running about. He used to love climbing trees. We’re hoping for more tree-climbing now,” Sally says.

- Luke with volunteer music therapist Brian

Luke Eccleston-Barnes, nine, has a needle phobia, perhaps because of the huge number of injections and blood tests he has endured in his life so far. But he is calm now – music therapist Brian Spears has arrived with his guitar to distract him while more blood was taken. He is playing softly to Luke, who tries to accompany him on an electronic keyboard Spears has brought along.

The nurses

Paediatric nurse Angeline Guzha and Dr Jana Kossaibati help a young girl called Sanaya in the paediatric intensive care unit.

Lilian Leite and Nimla Pentayya are two of the three sisters managing Rose ward, where they have both been for six years. Leite is from South Africa and Pentayya from Mauritius. “We wanted to travel and we stayed – we are getting job satisfaction here,” Pentayya says with a grin. Both always wanted to work with children.

We know that parents are upset and the young nurses are upset but we have to be strong, the three of us will support each other

– Lilian Leite

Dan Fossey is a practice educator, a nurse who trains other nurses. He also teaches parents basic life-support techniques in case they need them at home. Often parents are anxious and worry their child is too fragile. “Especially when they have had cardiac surgery they have questions about the scar and can you still do compressions,” he says. He teaches them to overcome their fears if a child has something stuck in his throat.

The last thing a parent wants to do is strike the child on the back

– Dan Fossey

Fossey runs a graduate programme for newly qualified nurses, to teach them about caring for children with heart defects. “I came here as a brand new nurse 10 years ago. I know what it’s like to come out of university and be looking after children with quite complex conditions,” he says.

Surgery

Abdula is being wheeled along a corridor to the operating theatre by robed staff, his mother trailing slightly – out of place and desperately anxious. By far the majority of the complex operations for congenital heart conditions carried out here are a success. Inevitably, sometimes they are not. In some cases, where there is a risk but the baby will die without an operation, surgeons as well as families have to be brave.

- Abdula Allanoud, four, on his way to his third heart operation

Consultant paediatric heart surgeon Olivier Ghez specialises in neonates – the tiniest babies, less than a month old, with a heart the size of a nut. He operates wearing binocular-style glasses that enlarge the miniature veins he has to stitch.

I have relatively small hands but it is the instruments, not the fingers

– Olivier Ghez

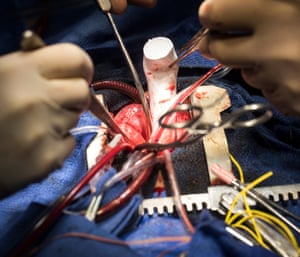

- Abdula is undergoing a four-hour Fontan procedure to correct a complex heart malformation, conducted by Ghez

Ghez’s job is exhausting – an operation can last three to five hours and a complex transplant could take 24 hours. But it is challenging and rewarding, he says. Sometimes he saves babies’ lives. Other times he gives them “the best possible future” with their heart condition. He can never be sure how it will go.

A 14-month-old girl, diagnosed after birth with a hole between the two chambers of the heart, comes into theatre for a relatively routine procedure and suffers a cardiac arrest. Suddenly the theatre is flooded with people, calm but purposeful, and the team restarts her heart.

- The girl arrested for four minutes during the procedure and was eventually revived by the team after a doctor performed CPR

When a child dies, says Ghez, “it is terrible, terrible – very sad and discouraging sometimes”. It may be a child who has had several successful previous operations at the Brompton. “When the baby dies after all this, it is really difficult,” he says. He worries about the accusations that can fly in the media over child deaths during or after surgery.

There is a danger of producing defensive medicine. That is a really perverse effect of the scrutiny. You can’t treat risky patients and have perfect results

– Olivier Ghez

Deaths are rare at the Brompton, but everyone is aware of the risks to the lives of these vulnerable children.

The support staff

A cleaner prepares to clear and disinfect a bay where an infection was recently present. Everybody is supportive. Theresa Dzade, one of the cleaning staff, says she likes the children and the parents.

It is not easy for someone to leave their house and come here with a small baby. They are sometimes sad because their baby is ill. They talk to me all the time. I tell them I am here to help – anything they want

– Theresa Dzade

Her friend Sidratu Kargbo feels the same.

We have to do a good job to make them happy

– Sidratu Kargbo

Night falls

Nursing and other medical staff work through the night as many patients require round-the-clock care. Parents usually leave the ward at night as they are encouraged by staff to rest.

Sandra Gala-Peralta, a PICU consultant, says: “If they don’t have a good rest, especially the mother, the following day they are exhausted. And if they are exhausted they don’t take the information in the same way. If something happens they are extremely fragile. So that is why we encourage them to go to sleep and have a good rest. If they don’t want to then we just let them be in the bed space. Especially if they are teenagers or children, five years old, then they have enough understanding to be be very afraid, so we let the parent in..”

- Abdula Allanoud recovers in intensive care after his heart operation

Gala-Peralta adds: “The evening tends to be a bit calmer. But everything depends on how the patients are. If the activity is high, the consultant stays around until … well, this is a personal choice. I’m more OCD, I like to make sure that if I go for a rest everything is in order and that I’m not going to have surprises in the night. We have an on-call room in one of the upstairs floors. I have been called in the middle of the night because a child has had a cardiac arrest. I was so stressed when they called me that I went down barefoot! I was doing cardiac massage in my socks! Now I’m more careful.”

I like to work on nights – it gives a lot of space to the doctor and nurses to focus on the patient, and because the night shifts tend to be a bit longer there is enough time to see how a patient can deteriorate, or improve during that time

– Sandra Gala-Peralta

- Gala-Peralta photographed at 8am at the end of a 24-hour shift

“There are nights when we sleep one hour … and there are nights when we are able to sleep four or five hours. At least we can put our head down and we can have a bit of rest every night. And then in the morning at 7.30 we need to be sharp, back on the unit,” says Gala-Peralta.

Inside Royal Brompton hospital"s paediatric unit – photo essay

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder