For many women living in Sudan, breast cancer means certain death. Treatment is too expensive or they simply feel too embarrassed to seek help.

But until recently, yet another obstacle was seriously hampering efforts to cut breast cancer deaths in Sudan. Since the early 1990s, the country has been on the US blacklist for state sponsors of terrorism – imposed for human rights violations and for harbouring Osama Bin Laden.

Even the Khartoum Breast Care Centre (KBCC), the Horn of Africa’s first and only dedicated breast cancer clinic, has been hit by the sanctions, with a ban on international money transfers and the restriction on imports of medical equipment and spare parts.

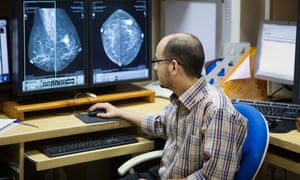

Founded by British-trained Sudanese radiologist Dr Hania Fadl, the KBCC offers hi-tech digital mammography screening for a fraction of the usual price elsewhere. Since it opened in 2010, it has treated more the 18,000 patients from across the region and has received widespread acclaim and international support.

Using private funds and a $ 14m donation from the charitable foundation run by her ex-husband, Sudanese-British businessman Mo Ibrahim, Fadl has managed its 11-year development from start to finish.

However, the US sanctions meant the centre was unable to buy and maintain crucial diagnostic machinery. In February 2014, it decided to begin a year-long application process for a US Office of Foreign Assets Control (Ofac) exemption, which would make it easier to maintain its General Electric digital mammography machine.

During the application process the machine broke down. It ended up being out of action for 10 weeks. The clinic was paralysed, with doctors forced to use alternative screening methods. “The problem is the poor women. You do ultrasounds and biopsies but an ultrasound is not an internationally approved screening modality,” Fadl says. “There are patients and I have to do something, even if they’ll put me in jail. I can’t let them wait and risk that their cancers spread.”

After heavy campaigning and several trips to Washington by Fadl to meet members of Congress, Ofac eventually issued a blanket licence exempting all medical equipment in Sudan from sanctions.

Ignorance is rife and I really hope and pray that women will come to the centre at least for a simple check up

The result was a welcome surprise to doctors at the KBCC, who say the move is a milestone for Sudanese healthcare in that it has put the needs of patients above international politics.

“All of our equipment in the clinic is from a US company, General Electric, as are the majority of advanced medical machines in Sudan. For there to be an exemption from sanctions, our lives as doctors will be much easier and the lives our patients will drastically change,” says Dr David Lawis, medical director of the KBCC.

Lawis says access to radiotherapy remains a huge issue, with just two machines in the country. One, in Khartoum a hospital, has been broken for about seven months. The second is in Madani hospital, two hours’ drive from Khartoum.

Anyone who can afford to pay for treatment abroad usually leaves Sudan to get radiotherapy, but the blanket Ofac licence has the potential to change this. “People won’t have to leave their country to get the treatment they deserve,” says Lawis.

Word of mouth

Other challenges remain, however, and Fadl says the battle to educate and inform women about self-examination and the local availability of affordable treatment is the next healthcare frontier.

“We did a little survey to ask the women how they heard about us. We found that the most effective, at 49%, was word of mouth. We are still a tribal community: we trust relatives, friends and neighbours who tell us ‘I went to that place and it is good’. We don’t have that culture of research on the internet,” says Fadl.

This was the case for 60-year-old Sudanese patient Fatma Abdelmajid, who regularly takes a six-hour bus from Atbara in north-east Sudan to Khartoum for treatment after a local doctor told her that “one of Atbara’s boys” worked at the KBCC clinic.

“The mentality around breast cancer here is absolutely wrong. When you tell women in the village that you’ve been diagnosed, they are so disturbed as if you’re about to drop dead in front of them. It’s really sad,” says Abdelmajid.

“They tell you, go to a fakeeh [spiritual healer], who will give you herbs and spiritual remedies to treat you. Ignorance is rife and I really hope and pray that women will come to the centre at least for a simple checkup.”

While the Sudanese health ministry keeps no full records, Lawis says that breast cancer accounts for approximately 35% of all cancer cases among Sudanese women. An estimated 60% of the 2,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer who die each year could have survived if given proper care.

Fadl strongly believes that stories like Abdelmajid’s will help end the taboo that often stops women from seeking a diagnosis. “A woman who has the experience of being treated should tell her stories, to new patients here at the centre and women in their villages. The best thing is to have these examples and success stories,” she says.

Fadl, who lives above the centre in Khartoum, patrols the corridors every day, greeting patients. “If I just walk downstairs and see the patients, see their kindness and deep gratitude, I just can’t help but want to help them. Sudanese women deserve everything I do – really and truly. I can’t tell you enough.”

Patients over politics: Sudanese breast cancer clinic that beat sanctions

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder