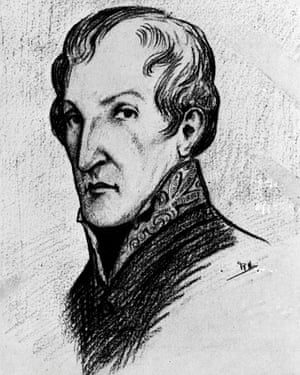

My idea of power dressing for success in the high-stress, male-dominated environment of medical school finals a decade ago was a smart blazer, hair in a bun and the strict avoidance of cleavage. Margaret Ann Bulkley, born in Ireland at the end of the 18th century, took things to another level. In her quest to break into medicine, Bulkley adopted an entirely male persona – it worked, and she emerged from Edinburgh University as the fully qualified Dr James Barry in 1812. This “beardless lad” served as a British army surgeon across the Empire for more than 40 years, her secret largely undetected.

Barry developed a reputation not only for her surgical prowess but also for her abrasive personality. After one unpleasant encounter, Florence Nightingale described her as a “blackguard”, writing that she “behaved like a brute”. Barry had a dog called Psyche and was prone to offering herself up for duels, including one over the establishment of a leper colony. Her close friendship with Lord Charles Somerset, governor of the Cape Colony, South Africa, where she was assistant surgeon to the garrison, led to rumours of a homosexual relationship – at that time, a capital offence in the armed forces. Somerset offered a hefty reward for the capture of the person who had spread gossip about the alleged “unnatural practices” and the rumours were quashed.

It was only on her death in 1865 of “diarrhoea” that the charwoman laying out her body discovered that James Barry was, in fact, biologically female. Stretch marks on her lower abdomen show that she may have even had a child. The Manchester Guardian described her life as “a supreme deception”, but acknowledged that she had been a brilliant surgeon.

Barry’s is not the only tale of cross-dressing in medical history – it echoes the tale of Agnodike, a fourth-century Athenian woman who is said to have cut off her hair and posed as a boy in order to study medicine under Herophilos, a follower of Hippocrates. Being a female doctor was a crime punishable by death, so Agnodike maintained her disguise, becoming a popular gynaecologist. Suspicious of her success, the male doctors accused her of seducing the women of Athens, an allegation she was only able to refute by lifting her skirts. Only her patients’ protests saved her from execution. While this story is likely to be apocryphal – dramatic skirt-lifting is a surprisingly common trope in ancient myths, and the only account of Agnodike’s life is from a shoddy Latin compilation of stories written hundreds of years later – the theme is familiar.

Women have always been intimately involved in medical matters – and not only through their familiarity with the act of expelling oversized babies from undersized pelvises. In the Middle Ages and beyond, women worked as midwives, nurses, apothecaries, bone-setters and surgeons. Yet, as the study of medicine became formalised, women were increasingly excluded. Henry VIII made a point of this in his 1540 charter forming the Company of Barber Surgeons, forerunner of the Royal College of Surgeons, in which it was decreed “No carpenter, smith, weaver or women shall practice surgery.”

By the mid-19th century, more women were demanding entry to medical school. The British Medical Journal at the time declared: “It is high time that this unnatural and preposterous attempt … to establish a race of feminine doctors should be exploded.” Men expressed concerns that exposure to gore might pose a risk to delicate female health, apparently oblivious that women deal with blood on a monthly basis.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, born in 1836, was the first English woman to qualify as a doctor. Despite her passion for studying medicine, not a single British medical school would accept her. Undaunted, she first enrolled as a nursing student, and then exploited a regulatory loophole to practice medicine by sitting exams for the Society of Apothecaries in 1865. She was the last woman to sneak in via this backdoor; the following year, it was closed. Garrett Anderson’s campaigning contributed to the 1876 “Enabling Act” that allowed the licensing of both male and female doctors.

This legal change wasn’t sufficient to thaw the antagonistic attitudes of most British medical schools towards women. But while teaching hospitals kept their doors shut, women set up their own hospitals. The coming decades would see more and more medical schools accepting women, and in 1892 the British Medical Association finally accepted female doctors.

The first world war allowed women to take up posts in hospitals that would ordinarily have been occupied by men. But despite their competence, female physicians still faced major career obstacles in the interwar period, including discrimination on the basis of their marital status. In 1948, the educational reforms that came with the inauguration of the NHS required that a “reasonable proportion” of medical students were female.

Today, female medical students outnumber their male colleagues. Currently, 45.4% of all registered medical practitioners in the UK are women. However, the proportion of senior hospital specialists who are women drops to 33.4%. The top echelons of medicine and surgery, especially senior academic posts, continue to be dominated by men. And there remains a significant gender pay gap.

Next month, Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones will be leading a group of runners on the Royal Parks half marathon in support of the Medical Women’s Federation, which celebrates its centenary next year. For the last hundred years, it has been committed to strengthening the position of women in medicine. We’ve achieved gender parity at intake for doctors in training – but when will we see it reflected in positions of power, and in our pay packets?

No scrubs: how women had to fight to become doctors | Farrah Jarral

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder