When you’ve been a food safety inspector for as long as Sharon Nkansah, you know how to smell a rat.

“Last month, there was a place I inspected [where] I walked in and you could smell it,” she says. “You can smell mouse activity. They had droppings in fridges, where they have their sauces, where they have their cutlery; the droppings were everywhere. So I just said: ‘Pull the shutters down’.”

You also learn tricks to catch out wily business owners. The best time to inspect a suspect business is in the morning, she says, before staff have had a chance to sweep up anything nasty deposited overnight.

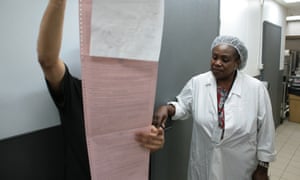

Nkansah has worked as a food safety inspector for Newham borough council in east London for 10 years. As we move between businesses throughout the day, she is fun and chatty, talking about her children and her recent holiday, but as soon as she’s in a kitchen, her bright patterned dress is covered with a white coat and her braids are tucked under a hairnet. She becomes brisk, businesslike, at times tough.

Her repeated refrain, delivered to staff at the takeaways she inspects who ask her for food hygiene advice, is: “I am not here to train you, I am here to enforce.”

A firm approach is needed in Newham. A Guardian analysis of Food Standards Agency data found that the borough has the lowest food hygiene scores in the country: 26% of its food businesses fail inspections, rising to 50.4% for takeaways. Far from being embarrassed by these numbers, Matthew Collins, a principal environmental health officer at the council, and Nkansah’s boss, sees them as a point of pride.

“I think it’s an indication that we’re out doing our jobs,” he says.

What food safety ratings mean

Nkansah began her career as a chef, but wanted a job with more child-friendly hours after having children, so did a one-year degree in food hygiene and began working as an inspector in Newham.

Cuts to local government funding have meant the number of food inspectors has declined in recent years. The ratio of food safety inspectors to businesses has dropped from 4.2 full-time inspectors per 1,000 food businesses in 2012-13, to 3.7 per 1,000 in 2014-15. This figure is dragged down considerably by England, where there are only 3.2 officers per 1,000 businesses, compared with 5.7 per 1,000 in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The job, says Nkansah, is satisfying, but it comes at a cost: she has seen what goes on in the back rooms of takeaways, cafes and restaurants.

Before going to a new restaurant, Nkansah says she always looks up its food safety rating. When asked if she would eat somewhere that scored zero, one or two, Nkansah is appalled. “Absolutely not,” she says.

On a good day, Nkansah can inspect three establishments. On a bad day, if she visits businesses where standards are very poor and the management is either belligerent or impossible to track down, she can spend half a day trying to evaluate one.

KFC: High Street North, East Ham

Nkansah starts at KFC on the high street. She is expecting big things here: large chains often do well with food safety and at its previous inspection in March 2014, this KFC branch was given the highest possible score of five.

Inside the KFC kitchen, the first thing Nkansah does is wash her hands. “It’s a way of testing if they have adequate hand-washing facilities. If they don’t, that’s not a good start,” she says.

KFC’s hand-washing station passes muster and Nkansah then works her way through the kitchen, starting at the entry point for deliveries, before moving on to the tills.

Nkansah is happy with everything – the general cleanliness of the kitchen, the way food is stored and the waste management system. The temperature of the freezer and fridges are good, and she is pleased to see a designated raw chicken preparation area.

“They’ve got good separation,” Nkansah says approvingly of the way the fridges are organised: raw chicken is stored on the left, while other products, such as milk, salad and Pepsi, are on the right.

“They will maintain their five stars as long as their paperwork is in order,” she tells me as we wind up.

When we leave the kitchen, two customers sitting down to chicken wraps and a large serving of chips look up at us, with our white coats and hairnets, in a concerned manner.

“Is it all right in there?” one man asks, voice lowered.

“Yes,” we assure him. “Looks good.” They nod and tuck into their meal.

King’s Peri Peri Chicken: High Street South, East Ham

Next is a visit to King’s Peri Peri Chicken. The inspection is a follow-up after the shop was given a score of zero, the lowest possible, in March. Nkansah is back to see if it has made improvements.

What were the issues at the last visit? “Oh, everything,” she says.

Most significantly, there was no hand-washing station, meaning that employees were either washing their hands in the large washing-up sink or not at all. Today, Nkansah is pleased to see that a hand-washing sink has been installed.

The manager is not in, so a staff member shows us around the property, starting with the food preparation area, which is in a basement below the shop. It is small and dark, and the floor is slippery with oil, but quite cool, which Nkansah says is a point in the restaurant’s favour. On the bench is a large plastic crate full of flour in which the raw chicken is tossed before being taken upstairs to be fried.

There are two other containers on shelves below the work surface, each holding flour, bits of which are stuck to the sides of the container with, Nkansah assumes, chicken juice. She worries that the same flour is used to coat chicken day in and day out.

The chef, who has been working at the shop for two weeks, struggles to understand Nkansah’s questions about how often they are cleaned, first saying they were cleaned every week, then every day and then every two days. It is unclear how much of this is a language barrier and how much is his uncertainty about the details of the cleaning schedule.

“I’ve been in this business for a long time,” says Nkansah, gesturing to the crates. “This is not today’s flour.”

Storage is also a problem: food should be kept on shelves off the ground. But a bag of rice and a sack of chicken breading mix, both open, and a bag of bread rolls, are on the floor. A large rice cooker sits in the corner of the kitchen next to cleaning chemicals.

Nkansah looks into the fridge, which she says is kept at a good temperature, and pulls out large open tins of jalapeños and olives, as well as a large uncovered saucepan of sticky sauce meant to go on rice.

“This is one of my pet hates,” says Nkansah. “I wouldn’t even do this at home, putting the whole pot in the fridge.”

She orders the staff to throw out the contents of the saucepan and both tins.

Nkansah revisits the shop a week later when the manager is in. He shows her the food safety paperwork. Because the shop had taken some measures to improve standards since the March inspection, it is rated up from a zero, meaning “urgent improvement necessary”, to a two, signifying “improvement necessary”.

As we leave the shop, we pass a long queue of people waiting to buy chicken and I wonder whether they would keep standing in line if they knew the store’s food safety rating. There is evidence that forcing businesses to display their food hygiene scores improves quality. When Wales made it mandatory for businesses to publicly display their ratings in November 2013, the proportion of places with a zero rating fell from 0.6% to the current rate of 0.2%. Northern Ireland will introduce a similar mandatory display policy on 7 October, but publicly displaying ratings is not mandatory in England or Scotland.

Agraba Grill: Barking Road, East Ham

The final visit for the day is supposed to be to a chicken shop, Peri Peri de Griller, which Nkansah shut down in July. She is back to see if it has improved conditions and can be allowed to reopen.

Instead, we find that the shop has been sold and a new store, Agraba Grill, has opened in the same location. It is in its second week of operation. The business is a Turkish takeaway, advertising kofta, kebabs and falafel wraps, but it still seems to sell a lot of fried chicken.

Again, the manager is not in, so someone who says he is a friend of the manager shows Nkansah the premises. Walking through the kitchen, the problems are immediately evident. The food preparation area, covering half of the kitchen, has no lights.

“Can I tell you one thing?” Nkansah says. “You cannot be running this food business in this darkness, it will not help you.”

She moves on to the other problems, among them the ceiling, which has a large hole, and an open drain. “You see, all these holes is where you can get cockroaches,” she says.

There are large piles of junk in the back of the kitchen – an old cooker, bags of rubbish and stacks of boxes. “If pests come in, they’re going to live in there and breed, so all the boxes and things you don’t need, they need to go,” Nkansah says.

There are other problems. There is no basin in the staff toilet – “So where do you think they’re washing their hands?” Nkansah asks, with a raised eyebrow – and she is unimpressed to find an ashtray in the kitchen.

“If someone is smoking back here, they need to stop, it’s illegal,” she says. Nkansah is immediately reassured that no one does.

Mostly, she is frustrated that conditions have not improved since the previous business was shut down. Places that are closed down cannot be reopened without being reinspected, but they can be sold on.

Owners of a new food business are required to register it with the council 28 days before they start operating, which leads to a food safety inspection, often within a month of operation. But this direction is frequently ignored and Collins says he knows of just one instance of a successful prosecution of a business for failing to register with the council.

Nkansah and Collins are adamant that the way to combat this problem is to introduce licences for food businesses, which would require owners to show proof of food safety training before they start serving customers.

Checking back with the council two weeks later, Collins tells me that the business has been sold again – the shop now has its fifth owner in nine months. The new proprietor is working with the council on improving standards at the premises before opening.

Back in the office, inspections done for the day, the food safety team are deciding where to go for a late lunch. But with the morning’s inspections playing on their minds, they opt for a safe bet: McDonald’s on the high street, food safety rating five.

‘Mouse droppings were everywhere’: a day in the life of a food inspector

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder