‘Life drawing”, “still life” and “life class” are all fairly mundane terms I thought only applied to nude figures or fruit bowls in an art studio. However, in November, I stood and drew in the corner of a plastic surgeon’s theatre in Lalgadh hospital, near Janakpur in Nepal. The theatre was set up to operate on the paralysed hands of leprosy patients. “Life drawing” became very appropriate very quickly.

Like many infectious diseases that predominantly affect those in poverty, leprosy is alive and well; there were more than 200,000 new cases were reported in 2015. The sad fact is that the disease is difficult to contract and relatively straightforward to treat. Many patients present late, when paralysis sets in. Although medication can make patients non-infective, the paralysis requires surgery to correct.

Each year, Working Hands – a Bristol-based charity run by hand surgeon Donald Sammut – spends two weeks, pro bono, operating on the backlog of patients in Lalgadh, training staff and providing hundreds of kilos of medical equipment and consumables. The work is highly skilled, but in many cases the objective is simple: to generate enough movement and power in a hand for the patient to go back to work, or to eat, or to look after themselves in a society where stigma is attached to those with the disease. Most of these patients are illiterate farmers whose only means of support depends on how much they can dig, or carry.

As I was drawing Raj, a 60-year-old man having an opponensplasty (an operation to restore strength and movement to a paralysed thumb), it occurred to me that there have been many crossovers between surgery and art. Leonardo da Vinci and Henry Tonks were two of them, both using drawing as a way of comprehending the human body.

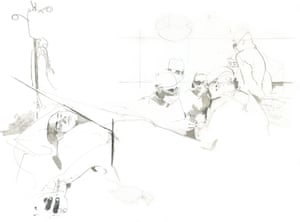

Watching Sammut, I could see why surgeons often make great artists. The value of being bold, with highly tuned hand-eye coordination, an obsessive understanding of what looks beautiful and a consideration for symmetry were all tips from the drawing books. But it doesn’t end there. Surgery is also performed under great time pressure; these procedures are all done under local anaesthetic, including the amputations, with a tourniquet to stem blood flow. The shorter the tourniquet time, the less damage to the tissue.

Before each surgery, Sammut spends several minutes drawing the patient’s hand; scar tissue shown with cross-hatching, deformity by weight of line, cut lines with dotted lines. “Those few minutes of examining and drawing the hand are invaluable,” he says. “While drawing, one is obliged to examine every millimetre, the texture and suppleness of the tissues one is about to rearrange. And it also gives one a few moments to plan the surgery, running it through one’s head like choreography steps.” The drawing is the beginning of a relationship built on trust, and a life-changing procedure.

Leprosy patients here are treated at Lalgadh hospital for free, supported by the 400 paying outpatients the hospital treats each day.

An entire family collecting hay, typical of the sort of agricultural society that many of the leprosy patients work in.

Two patients waiting in line for physiotherapy after corrective surgery on their hands.

A Hindu funeral pyre for 55-year-old Krishna Bikram Chauhan on the bed of the river Sundari near Janatpur. The names of those watching the pyre are taken and they are invited to a celebration 10 days later.

A mother comforts her child after his operation.

Working Hands team and local doctors in the middle of a procedure in Lalgadh hospital.

The art of surgery: life drawing and leprosy