In accordance to a newly published study, wild mice often and voluntarily run on an exercise wheel if presented entry to them in nature, even in the absence of a food reward. Further, the length of operating bouts by wild mice matched people of captive mice. These findings dispel the concept that wheel running is an artefact of captivity, indicative either of neurosis or a mindless repetitive behaviour (stereotypy) that may possibly be connected with poor welfare or close confinement.

In accordance to a newly published study, wild mice often and voluntarily run on an exercise wheel if presented entry to them in nature, even in the absence of a food reward. Further, the length of operating bouts by wild mice matched people of captive mice. These findings dispel the concept that wheel running is an artefact of captivity, indicative either of neurosis or a mindless repetitive behaviour (stereotypy) that may possibly be connected with poor welfare or close confinement.

Action wheels come in a range of sizes and styles, but their simple objective is to supply confined animals with the possibility to workout, as you see these adorable dwarf hamsters doing here:

Reading through on a mobile device? Here is the video hyperlink.

Which is an amusing video, and the hamsters seem to be enjoying themselves, but are they genuinely? And how may possibly you figure this out?

I ran across an fascinating minor research paper that addresses a basic — and controversial — question in exercising physiology: is operating in an exercising wheel an artefact of captivity as exhibited by small pets, like hamsters, mice and rats? Why do they do it? Is it intended to alleviate stress or neurosis brought on by near confinement, is it a repetitive and invariant behaviour that is devoid of any apparent goal or function (stereotypy), this kind of as cage-pacing observed in some zoo animals, or may possibly it signify some thing else?

“When it comes to stereotyped behaviour, there are competing theories. One problem, as an example, is no matter whether stereotyped behaviour is a symptom of negative welfare that must be prevented, or whether or not it is a coping technique that in fact increases welfare”, explained the study’s co-author, Yuri Robbers, in email.

Mr Robbers, who works as a grammar college biology teacher, has a master’s degree in animal behaviour and is presently researching animal behaviour, theoretical biology and ecology as he performs towards his PhD underneath the mentorship of neurophysiologist Johanna H. Meijer, a professor in the Department of Physiology at the Leiden University Healthcare Center in The Netherlands.

The controversy swirling close to running on an exercise wheel worried the Dutch researchers so much that they developed numerous experiments to clarify the basis of this behaviour. Particularly, they desired to check whether or not wheel operating fulfills the criteria for a stereotypy: (one) it happens only in captive animals, (two) it is repetitive, invariant and devoid of obvious objective or function, (three) if it consists of all-natural behavioural elements, these factors take place at larger rates and for longer durations than located in nature, and (four) it is partially or not at all dependent on external stimuli.

Will wild mice use a operating wheel if a single is supplied in nature?

Popular animal behaviourist Konrad Lorenz once remarked that rodents that had either escaped or been launched will enter and run on physical exercise wheels if one particular is accessible to them (as cited here: doi:10.1126/science.155.3770.1623). Intrigued, Professor Meijer and Mr Robbers decided to comply with up on this observation by going one stage even more: they asked whether cost-free-residing animals that had in no way prior to observed an activity wheel would voluntarily use a single if it was accessible to them.

They made a cage that exclusively excluded large animals (so they would not knock more than the workout wheel set up). Within this cage, which could be freely accessed by little animals, they placed a operating wheel along with some foods intended to appeal to mice. These exclosures had been set up in nature at two various discipline sites a green urban location (Professor Meijer’s back garden) and a dune region that was inaccessible to the public (see below):

Every single pay a visit to to the experimental set-up was recorded by a evening-vision camera, employing passive infrared movement detection. At evening, the camera relied upon infrared light (infrared light is invisible to mice), which did not interfere with movement detection.

Data have been collected for far more than 3 years utilizing this experimental set-up (green urban location information had been collected from October 2009 to February 2013, and dune area information had been collected from June 2011 to January 2013 figure two):

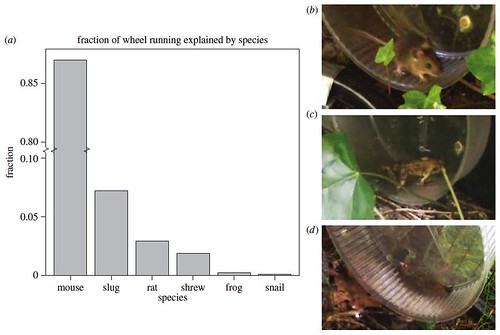

The operating wheels proved well-known with a range of cost-free-residing animal species. More than time period of above three years, Professor Meijer and Mr Robbers manufactured much more than 200,000 recordings of animal guests and analysed far more than 12,000 video fragments in which wheel movement was detected.

In the 1st 24 months, the urban green location resulted in 1011 animal visits (of which 734 were mice). The very first 20 months in the dunes resulted in 254 animal visits (of which 232 were mice). Even though the cage was baited with foods exclusively intended to appeal to mice, other animals — shrews, rats, snails, slugs, and frogs — also stopped in to do some running (or sliming?). Interestingly (to this ornithologist), even small birds popped in occasionally, although they were in no way recorded operating on the wheel.

“Our information signifies that wheel operating takes place in nature, getting performed by free-living wild animals”, said Mr Robbers. Hence, “captivity, extended or otherwise, can not probably be the cause of wheel operating”. Considering that all the professionals agree that stereotypical behaviours only occur in captivity, wheel operating does not match properly into the criteria.

In view of the broad variety of diet programs favored by these other species of animal guests, it would appear they had been not coming solely for the foods. So of course, Professor Meijer and Mr Robbers then asked what would occur if they stopped delivering any meals at all — might these animals still pop in for a run on the exercise wheel?

Will free of charge-residing animals use a running wheel with no a foods reward?

Though Professor Meijer and Mr Robbers stopped offering food in the urban area enclosures for far more than a year (October 2011–February 2013), animal visits continued. Professor Meijer and Mr Robbers observed 78 wheel working visits (62 mouse visits — 36 of which had been very little mice, indicating they had been as well youthful to know the cages had previously been baited with food).

The information exposed that the quantity of visits to the exercise wheel dropped drastically as quickly as the food was removed, but visits that incorporated wheel running really enhanced by 42 %, indicating that the animals (wild mice, mostly) were visiting the cage particularly to run on the action wheel, that workout is rewarding in itself. The experimental device acts as a type of neighbourhood mouse fitness center, it would seem.

Were action bouts comparable in between wild and lab mice?

Yet another test of regardless of whether wheel running fulfills a behavioural stereotypy was to examine wheel operating exercise among wild and lab mice. To get a clearer image of the animals’ exercise patterns, Professor Meijer and Mr Robbers in contrast wheel-working information from their wild mice to wheel-running data from laboratory mice that had been collected previously by another researcher (doi:10.1126/science.155.3770.1623, see figure 3):

The data reveal that most of the wheel working mice had been juveniles, and 20 % of them had bouts that lasted longer than one minute, with the highest bout lasting 18 minutes. This is comparable to activity bouts was reported for 200-day old lab mice that were closely confined.

The wild mice have been truly functioning tough, also: despite the fact that the common speed of running was slightly much less than for lab mice (one.3 versus

two.three km/h), the highest running velocity observed for wild mice was higher

than the highest for lab mice (five.7 versus five.1 km/h).

Why do wild mice voluntarily run on workout wheels?

This study displays that wheel working is voluntary in wild mice, is not dependent on a food reward, and takes place in bouts that are comparable to those recorded for captive mice, so it does not satisfy the established criteria for a stereotypical behaviour, as some scientists have argued. Of course, this raises the query: why do they do it?

“We’re considering perform behaviour as a viable explanation, and have started follow-up experiments to test that hypothesis”, said Mr Robbers.

Wheel operating looks rather uninteresting (suggestive of my least favourite piece of health club equipment, the treadmill), but probably these animals see an exercise wheel similarly to humans when given the choice to climb musical stairs as an alternative of riding an escalator, as we see in this video?

Reading on a mobile device? Here is the video hyperlink.

Why do we care about mice and their exercise wheels?

As anybody who reads the newspapers or listens to the radio knows, we are daily told to get much more workout. Fundamentally, everyday physical exercise slows ageing, reduces the incidence of many cancers, assists maintain a affordable physique weight, reduces the incidence of diabetes, heart assault and stroke, and improves brain function — and that is just to name a couple of benefits that I have read about this week. Investigation into the human wellness advantages of bodily activity depend upon the use of running wheels employed by lab animals. If this wheel running is a stereotypy, this could be problematic.

“Some scientists … have had a tendency to dismiss study findings based mostly on the use of operating wheels outright,” explained Mr Robbers in electronic mail. “This is rather much more challenging, now that our information is there to propose that wheel running can take place in totally free residing animals.”

Reading through on a mobile device? Here’s the video hyperlink.

Sources:

Meijer J.H. & Robbers Y. (2014). Wheel operating in the wild, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281 (1786) 20140210-20140210. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0210

Yuri Robbers [emails 17, 18, twenty & 21 May possibly 2014]

A lot of thanks of course to my twitter followers who kindly sent at lightning pace the PDF I requested @GOrizaola, @ConservResearch, @Rob0Sullivan, and @_inundata.

Also cited:

Sherwin C.M. (1998). Voluntary wheel running: a review and novel interpretation, Animal Behaviour, 56 (1) eleven-27. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.0836

Science&rft.artnum=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.sciencemag.org%2Fcgi%2Fdoi%2F10.1126%2Fscience.155.3770.1623&rft.volume=155&rft.situation=3770&rft.issn=0036-8075&rft.spage=1623&rft.epage=1639&rft.date=1967&rfr_id=information%3Asid%2Fscienceseeker.org&rft.au=Kavanau+J.+L.&rft.aulast=Kavanau&rft.aufirst=J.+L.&rfs_dat=ss.incorporated=1&rfe_dat=bpr3.integrated=1bpr3.tags=Biology%2CPsychology”>Kavanau J.L. (1967). Habits of Captive White-Footed Mice, Science, 155 (3770) 1623-1639. doi:10.1126/science.155.3770.1623 [Open access]

.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

When she’s not doing work out in the fitness center or running up the stairs to her flat (located on the 13th floor), GrrlScientist can also be found here: Maniraptora. She’s very lively on twitter @GrrlScientist and occasionally lurks on social media: facebook, G+, LinkedIn, and Pinterest.

Wild mice in fact appreciate running on physical exercise wheels | @GrrlScientist

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder