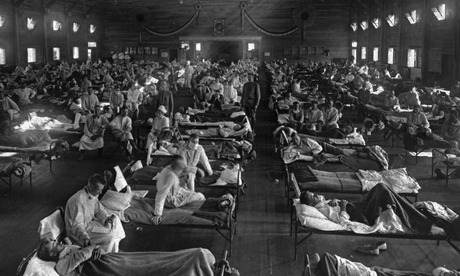

A Spanish flu ward at Fort Riley, Kansas, in 1918. Reseachers insist that the ‘only way to guard towards another deadly outbreak is to produce viruses very related to these responsible’. Photograph: AP

There may possibly be a fatal tumour in your brain. The only way we’ll know is if I cut it open – but there is a possibility that may possibly destroy you. Shall I go ahead?

We’ve just been confronted with a question a bit like this by scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. They insist the only way to guard towards the outbreak of a deadly flu epidemic like the Spanish flu of 1918 (pictured right) is to produce viruses really equivalent to those accountable. Not to review them in the wild, mind, but to actively engineer from bird flu genes a strain that can pass in airborne droplets from one animal – or possibly species – to another. Certain, it is hazardous. But what about the chance of carrying out absolutely nothing?

So – should they go ahead?

Not in accordance to Sir Robert May, one of the world’s most respected epidemiologists. Publicly he has called the work “completely crazy”, and offered May’s status for directness his private viewpoint is likely to be much less polite. He’s not alone. Other researchers have challenged the claims of the Wisconsin group that their operate is the only way to find out how to fight a lethal flu outbreak properly, and that the experiments have been deemed needed and protected by authorities. May possibly even suggests that the group efficiently hoodwinked the US Nationwide Institutes of Health into granting approval and funding.

Investigation on pathogens, particularly viruses, has turn into increasingly disputatious more than the previous decade. In 2002 a team at the State University of New York ordered pieces of synthetic DNA through the mail, from which they pasted with each other the genome of the polio virus. They then “booted it up” to infect mice, explaining that the operate had been done to highlight the danger of how simple it was. Other individuals accused the staff of an irresponsible publicity stunt. The Wisconsin group, led by the virologist Yoshihiro Kawaoka, courted controversy in 2012 when it produced a mutant strain of H5N1 bird flu that could spread between mammals. Its final results, and comparable ones from a staff in the Netherlands, have been deemed also dangerous to publish by a US biosecurity panel that feared what bioterrorists may possibly do with them.

In one particular sense we have been here just before. Investigation often carries risks, no matter whether of intentional misuse or accidents. The discovery of nuclear vitality in the early 20th century, and of how to release it by way of nuclear fission in 1938, were arguably examples of “pure” research with perilous applications that nonetheless loom apocalyptically right now. The frequent response of scientists is that this kind of is the inevitable price of new information.

But the dangers of biotechnology, genetics and synthetic biology are anything new. For centuries we struggled to keep nasty microorganisms at bay. Even the discovery of antibiotics gave us no protection from viruses, and the emergence of HIV was a bitter reminder of that. But with the arrival of genetic manipulation in the 1970s, nature was no longer an inscrutable menace warded off with trial-and-error potions: we could fight back at the genetic degree.

This new signifies of intervention brought a new way to foul up. Synthetic biology promises to consider the battle to the up coming level: to move beyond tinkering with this or that resistance gene, say, and to enable total-scale engineering and layout of existence. We can consider our nemeses apart and rebuild them from scratch.

Yet we arrive at this point fairly unprepared to deal with the moral dilemmas. The heated nature of the present debate signifies as a lot: scientists have by no means been averse to shouting at every single other about the interpretation of their benefits, but it is uncommon to see them so passionately opposed on the question of whether or not a piece of research ought to be carried out in the first spot. If even prime specialists can’t agree, what is to be carried out?

Physical scientists are typically faced with questions that can not be answered experimentally not, on the complete, simply because the experiments are too unsafe – but because they are as well challenging. Their normal response is to figure out what need to come about in concept, and then see if the predictions can be examined in much more accessible, less complicated approaches. But in biology it is significantly, a lot more difficult to make trustworthy theoretical predictions (or any predictions at all), because living items are so damned challenging.

We’re getting there, nevertheless, as witnessed by the advancement of computer designs of human physiology and biochemistry for drug testing. It really is not too much to hope that one day medication might be made and securely trialled practically wholly on the computer, with no the need for controversial animal tests or pricey human trials. Other designs may be sufficient for knowing viruses, which are following all the simplest organisms identified. One particular purpose why some researchers argue that remaining smallpox stocks be destroyed is that the reside virus is no longer required for research – its genome sequence is sufficient. Looked at this way, generating hair-raisingly lethal viruses to comprehend their behaviour displays our lamentable ignorance of the theoretical rules involved.

There could be techniques to make experiments safer too. Faced with fears about the quasi-artificial life kinds they are beginning to generate, synthetic biologists say that it must be achievable to create in safety measures – for example, so that the organisms can only survive on a nutrient unavailable in the wild, or will self-destruct following a couple of rounds of replication. These are not fantasies, despite the fact that they raise questions both about whether such fail-secure methods give natural variety even more urgency to evade them – and regardless of whether there is a false protection in the whole engineering paradigm when applied to biology.

All the very same, the concerns raised by flu study cannot be defused with technofixes alone. Fail to remember the new Longitude prize – here is a location exactly where science truly does require to be democratic. A single thing you can say for positive about the question posed at the outset is that the patient must have a say. If scientists are going to consider these hazards for our sake, as they declare, then we had far better be asked for our approval. It truly is in our interests to guarantee that our determination is informed and not kneejerk, and the appropriate democratic machinery needs cautious construction. But the consent must be ours to give.

Experimenting with a new Spanish flu is everybody"s organization | Philip Ball