My granddaughter killed herself because the rent was due. She was 21. She left her parents a note. In part it read: “I’m about to do something ungodly. I’m sorry.”

In retrospect, she was hell-bent on self-harm. I don’t know what her body did to offend her, but for the last half decade of her life she punished it without remission. She extended the maltreatment to her immediate family, excoriating her mother, defaming her father, denouncing them to her brother and sister. Then she moved out “to be free”, and spent the next subsidised 18 months resisting every available mode of occupation or trade or pastime, insisting that all she really wanted to do was to “come home” – the home where the seeds of persecution and victimisation were allegedly sown, the home where anorexia took root and bulimia blossomed, the home where even she had begun to see that she was ill.

Yes, from time to time she accepted that she was ill and presented herself to those who could provide custodial intervention and sufficient carbohydrates to enable her to insist that she never had been other than entirely well, and whose domestic or institutional havens she would then renounce so that she could starve herself into the commencement of the next cycle. Every tactic contradictory, every endeavour repercussive, obviously she was on the path to self-destruction. In retrospect.

Every spate of professional counselling added to her education in the methodology of professional counselling. Each medical intervention augmented her command of its jargon. On her last admittance to Toronto’s prime psychiatric facility, sufficiently refreshed by a few days of its available stodge, she opposed remaining there long enough for a diagnosis to be accomplished, and she argued for her release at an official tribunal during which she held her own against a panel of psychiatrists, social workers and ward supervisors for four hours – a hospital record for duration – and ended the marathon by offering to return on a voluntary basis to provide art instruction to the inmates who, unlike her, needed to be incarcerated and, in her estimation, were bored.

On this occasion as on all the others, her glib protest was accepted. She was adjudged to be no danger to herself or to anyone and was released, doubtless to the sound of a vast institutional sigh. Meanwhile, in her private journal she reiterated that her ideal body weight was 88lb (40kg). These aspirations were accompanied by illustrative sketches of herself, redolent of Auschwitz.

Emma’s default vision was black. It was where she felt most comfortable. When she was 10, my wife and I took her to an owl sanctuary near our home in Bath. I need no photograph to recall her expression when a 10lb self-guided feather-bomb with a six-foot wing-span, a great grey, skimmed the surface of a meadow and landed on the leather gauntlet Emma wore and which I helped her to support. Yet, within the 20-minute interval of the return drive, she’d subjected ecstasy to her typical revisionism. By the time she emerged from the back seat, the excursion had been converted into “the worst experience of my whole entire life”.

Once again, she’d consumed pleasure at the moment of delivery and then divested herself of its nutritional value, perhaps because something in her knew what followed happiness, and she feared it and pre-empted it with its inevitable consequence.

On her last transatlantic visit, Emma was escorted by my younger daughter who sacrificed much of her own tranquillity to her niece’s wilderness years. We took them to Rudyard Kipling’s garden at Rottingdean, near Brighton. The day was hot, the garden abloom with mid-July. Along the corkscrew path, Emma lagged behind, reportedly vigilant of insect life and its poisonous sting. To my backward glance she was luminous in the haze, joyous, incandescent and reckless as any rose.

That outing features largely in the scrapbook she compiled to commemorate the trip. She rarely completed any project. She completed this one. Uniformly enthusiastic, touchingly adolescent, unbearably normal, the scrapbook contains no hint of anxiety, not a blemish of doom. Apparently, she was able to acknowledge pleasure in recollection when she was insulated by paper from the sting of its worldly process. On the occasion of Kipling’s garden, it took my intervention to nudge her along her wonted course … the spiral to despair.

At supper that evening, I made her cry by pointing out that her description of her fellow students at art college as “retards” was offensive and a tad judgmental. To my daughter, who spotted impending tears and intervened to spare her niece further abuse at my hands, she whispered, “It’s as if he doesn’t like me.”

Later, she spun the incident and memorialised it in her scrapbook. “Papa Jack,” she wrote, “says sad things.”

In truth, Emma’s decline didn’t improve any of us unless, in the Catholic sense, by making us disproportionately conscious of our futility and lack of grace. My mother, however, was Jewish as, through the maternal line whether they will it or not, are my daughters and, therefore, theirs and theirs. Even among the least orthodox Jews, suicide continues to bear a tincture of abomination … something that invites a very Jewish spasm of self-blame. I shouldn’t have made her cry. I should have withheld my inhospitable corrective, deferred my display of liberal credentials, suppressed my pedagoguery, my self-aggrandisement, my vainglory. True enough, some of it. And none of it explains the fact that she’s gone.

An exaggeration of her virtues honours her as little as an extirpation of her faults. In a life as short as Emma’s, every action is notable, every event historic. Besides, doing it doesn’t work. The greater our distortions and omissions, the more the recollection of her performance corrects them. What also doesn’t work is regretting the years she might have had. They never were hers. Twenty-one of them were, and are hers still to occupy and expend as she did. Any more are in the possession of some other Emma, the one we encounter nightly who departs at dawn.

The statistics were against her. For women between 15 and 24, eating disorders have been claimed to incur the highest mortality rate of any mental illness, 12 times higher than that associated with all other causes of death for that age group … significant when applied to the population; meaningless when measured by the criterion of one. Faced with the particularity of Emma, everyone looked elsewhere and hoped otherwise and was disappointed.

There always was a surfeit of available explanations for Emma’s irrational conduct. Self-dramatisation, attention-seeking, shortcuts to fame, laziness, hormones, bad seed … there’s a clarity, a sensibleness, a sameness to them all, the inexorable logic of those convinced of their own rationality.

And now there’s something about Emma’s death that encourages interpretations that never quite apply and illuminate the interpreter more. Sensibleness is their least common denominator. Her last social worker – over the years she had several; he was her favourite – called her decision to step off the top floor of her six-storey Montreal apartment building “an existential tantrum”. At her bleakest, her mother suggested it was “logical”. I think it was an accident based on a flawed assessment. In an ecstasy of starvation, a gossamer dream of abnegation, she believed she’d rise, not fall. The ungodly thing she was about to do was fly.

I remember Emma’s first trip to Niagara Falls with this grandfather who hated heights combined with the motion of rushing water, but had decided to “man up” in front of his six-year-old firstborn third generational who wasn’t afraid of them or of anything else. Careening down the highway, I heard a grunt beside me. Her gumdrop had popped out of her mouth. She bent forward, recovered it from the grubby floor mat and contemplated it lovingly. “Throw it out the window,” I said. She looked at the hairy gumdrop in her hand, glanced up into my profile and back to the gumdrop. I could hear the clicks as her brain calculated the probability of my relinquishing the steering wheel to confiscate the contaminated sweet. “No way,” she said, and rammed the gumdrop home.

Then she moved from Toronto to Montreal to be free. And then the rent came due. And she’d already spent it.

• In the UK, the Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123.

In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Hotline is 1-800-273-8255.

In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is on 13 11 14.

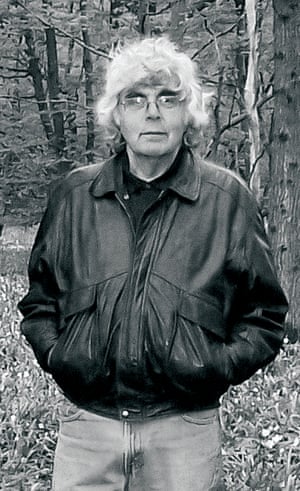

My granddaughter, the girl who refused to let joy into her life

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder