Exactly four years ago, surrounded by placards saying “Equality” and “Rights”, Junior Sterling was performing to millions of people in London’s Paralympic opening ceremony. But despite all the talk of the Games’ legacy for disabled people in Britain, the 55-year-old, who was born with a muscle-wasting disease and club foot, has been left to live in a kitchen covered in mould and with a bucket for his bathroom.

In his one-bed council flat in Shepherd’s Bush, west London, Junior talks avidly about London’s Paralympics in 2012. He was a volunteer Games Maker, working as a steward at the wheelchair tennis, and part of the famed “Spasticus Autisticus!” segment of the opening ceremony. In the run-up to the Games, Junior even had his photo taken with Sebastian Coe after creating a sign spelling out 2012 in braille. What no one realised, however, was that after spending his day around Paralympians, as Junior puts it to me: “I’d go back to my home infested with bugs.”

Junior has been in this flat for 20 years; his first home after eight years of, in his words, “living in cardboard boxes” on London’s streets. The flat is on the top floor of the block, up three flights of steps and there’s no lift, which isn’t ideal for someone who struggles to walk. But Junior took the flat, afraid that if he didn’t he’d be sent to the bottom of the council’s housing list.

The problems inside the flat started several years later, in 2002. At first it was a simple problem with his shower. By the time of London 2012, the plumbing had got so bad through the whole flat it had flooded Junior’s downstairs neighbour causing their shower tiles fall off. Filter flies, drawn to drains and sewage, contaminated his bathroom.

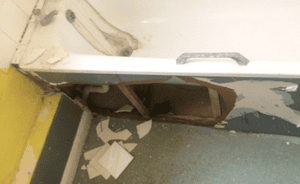

Since then, little has changed. In fact, it’s got worse. As of this summer, Junior has been without a working bathroom or kitchen for five years. The shower is disconnected and the bath has a panel missing. Damp and mould cover the ceiling and walls. The housing association responsible for the accommodation, Peabody Trust, got rid of the fly infestation but the stench remains, Junior says. The kitchen sink is still bust; Junior’s been told by the manager of his housing block not to use it (water leaks down the walls of the neighbour beneath him).

The effects of the damp then spread into the front room. The carpet is cut up – a scrap left in the middle of the floor – and a loaf of bread, tinned milk, tuna, and corn flour are stacked on the furniture. The water and mould in the kitchen means Junior has to keep the food where he sits, but flies are attracted to it, especially when it’s hot.

Junior has contacted Peabody housing association repeatedly over the years – he shows me a journal he’s kept of it all, 10 pages going back over a decade – but says he’s barely heard a whisper back. Still, they keep collecting the rent: £129 per week, paid straight from Junior’s council. He says when he does hear back from them, Peabody claims it’s not been able to get in touch with him. “They make so much money, but this? They can’t sort this.”

A Peabody spokesman offered to put the wheels in motion to sort the problems out, stating that the team had already tried to resolve them, but that the last contact they had with Junior was in March 2015. “Prior to that we worked extensively with the council and our contractors to draw up a specification of works. These were unable to be completed as the contractor was repeatedly refused entry by the tenant,” he added. “Mr Sterling has declined to deal with us directly, insisting that all communication went through his solicitor. If Mr Sterling would like our contractor to make fresh inspections and carry out repairs, he will need to get in touch and let them into the home.”

Junior says someone from Peabody came to take pictures of his flat but he is unaware of anyone trying to the carry out the necessary work. He had a solicitor to help him for three years, but without legal aid he was unable to take the case to court. In the meantime, he can barely keep clean. The toilet in his bathroom flushes but because of the damp and the smell, he’s afraid to go in there. Instead, a toilet for Junior is now “a bag and a box”. With no working shower, if he wants a shave, he gets water from a hose outside the flat. Two buckets for when he needs a wash.

Because of the kitchen leak, it’s the same routine each time he has a hot drink. “If I want tea or coffee, I have to fill up a water bottle,” he says. “Go down [to the hose]. Fill it up with water. And then do it again.”

Anyone’s health would get worse from living like this, but when you’re disabled, it’s devastating. Junior’s two stone lighter now (“I can’t eat in the flat”) and the mould gives him recurring chest infections. Not being able to shower or bathe for years has led to him losing his hair through dry skin, and his feet – already vulnerable – are now covered in callouses.

Junior still has his London 2012 Paralympic band around his wrist. “I can’t tell you the tears I’ve cried,” he says. “I may as well be homeless again.”

Junior was a London Paralympics Games Maker. Don’t talk to him about ‘legacy’ | Frances Ryan

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder