In the packed frequent room at a sheltered housing community in south London, groups of pensioners sit eagerly poised above their bingo cards, felt-tip dabbers at the prepared. It is the social highlight of the week, but there is an uneasy feeling in the air, with an imminent pay a visit to from the council looming on the horizon.

“They want to kick us out,” says Richard Newman, 91, who has lived here for 7 many years. “They are going to sell off the land to create housing, and move us into an institutional tower. Here I can be fully independent – I still go to the store, cook my own food, run a bath – but they want to throw us into an infirmary. They’ve got no compassion whatsoever.”

Over the last few months, the residents of 269 Leigham Court Street in Lambeth have come with each other to campaign towards the “disposal” of their neighborhood, which the council programs to sell to fund the construction of “further care” housing elsewhere in the borough.

“They call it ‘extra care’ because it really is more like currently being in hospital,” says Joyce James, 89. “We reside here like a family we will not want to be separated from one yet another. And the buildings are magnificent – it would be like pulling down Buckingham Palace or Westminster Abbey. It truly is criminal.”

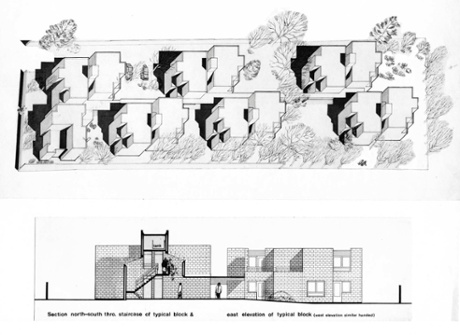

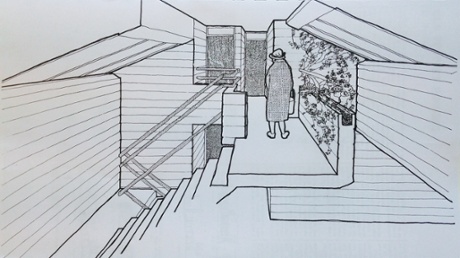

Made in the early 1970s, a single of Lambeth’s 1st experiments with modular building, the spot has a lot more in frequent with the crisp cubic forms of Bauhaus villas than the dumpy semis of suburban Streatham. Extending back into a deep, leafy plot from a narrow street frontage, the 44-flat complex is composed of staggered clusters of blocks, organized in a loose chequerboard either side of a central covered walkway. With faces of raw concrete block-function, stepping back to kind terraces and private patios, the huddles of homes frame shrub-fringed lawns amongst their sharply sculpted volumes. It has the feeling of a present day monastery, quiet cloisters dotted with mature trees, views cautiously framed between the walkway’s colonnade.

It is the perform of architect Kate Macintosh, who arrived in the borough’s architects department in 1968 fresh from Southwark council, in which she had designed the huge 300-unit housing complex of Dawson’s Heights in East Dulwich, at the tender age of 27. A pair of majestic brick ziggurats that kind a pixelated mountain assortment on the horizon, it was a startling arrival to its south London website, inspired by the clustered cloud of Moshe Safdie’s Habitat housing, created for the 1967 Montreal expo.

“Both of these schemes have been driven by a preoccupation with trying to express the personal dwelling within a significantly larger overall complicated,” says Macintosh, when we meet at Leigham Court Street. “We have been fighting against the blunt anonymity of the monotonous slab blocks that had been popping up all over the place at the time.”

Possessing won a scholarship to Warsaw Polytechnic while she was a student at Edinburgh, Macintosh then spent time working for architects in Stockholm, Copenhagen and Helsinki, in an setting that influenced the rest of her profession. “It was a stark contrast to Britain in the 1960s,” she says. “Scandinavia felt like a significantly a lot more egalitarian society, where girls have been more innovative in the profession, and there was significantly less resistance to modern day architecture. There was just no argument.”

Returning to London in 1964, she joined Denys Lasdun’s workplace to function on the Nationwide Theatre, where she was put in charge of creating an experimental auditorium, which would grow to be the Cottesloe Theatre. When responsibility for social housing provision passed from London County Council to the boroughs in 1965, she created the leap to the public sector, seeing the massive chance for radical innovation. Soon after three years at Southwark, she was tempted to join Lambeth right after seeing the sketches for Lambeth Towers, by her future husband George Finch, on the cover of the RIBA Journal.

“It was really like at very first sight,” she grins. “I just had to meet the man that had developed those buildings.”

In Lambeth she joined the research and improvement department, just as a new government policy was introduced to motivate modular development. “It was a national energy to coordinate the dimensions of developing materials,” she says, “to join up companies with designers and builders, at the exact same time as the transition from imperial to metric. I believed the R&D division would give me some theoretical backup on the mysteries of modular coordination.”

Hailed in Constructing magazine at the time as “the London Borough of Lambeth’s initial wholly metric dwellings,” 269 Leigham Court Street was a radical departure for the council, using lightweight concrete blocks, rather than bricks, at Macintosh’s behest.

“I favor to restrict the range of materials and look for to obtain visual curiosity by way of the modelling and relationships of kind and room,” she wrote in Architectural Design magazine in 1975, in a characteristic on Leigham Court. “The more substantial scale [concrete block] units and simplicity of detailing give it a considerable physical appearance which I felt acceptable to this scheme.”

Accompanied by a sparing palette of stained brown timber and tubular steel balustrades, the two-layer block-operate development kinds a considerable armature that has stood the check of time. The sculpted prime-lit entranceways, the place communal landings lead off from concrete staircases, give a feeling of robust security, with a spatial sequence crafted to stability the requirements of privacy with sociability.

“I thought of the covered way as a stream of water, with spaces for little eddies to occur off the stream,” says Macintosh. “Carving out areas for people to sit and gossip, and mill in and out.” The route kinks along its length, to keep away from an limitless institutional vista, although there is seating developed in to nooks and crannies, pockets minimize into the strategy.

“Individuals are often stopping to say hello and have a chat along this path,” says Valentine Walker, 63, who moved here three years in the past following suffering from depression. “It’s a truly sociable place, but we have our very own private gardens close to the back also – some thing to hold the thoughts innovative.”

“It is the perfect balance of possessing my very own area, but feeling part of something greater,” says Linda Lee, 61, sitting in her light-flooded living area, searching out by means of full-height windows on to the lawn beyond. “I really like the feeling of obtaining individuals around, but not being invaded. And the grandchildren love tearing around on their scooters.” She has only been here for six months, but can’t picture leaving. “I would be devastated to go,” she says. “Nowhere else is going to really feel like this.”

The Twentieth Century Society, which unsuccessfully fought to get Dawson Heights listed, has lent its weight to the campaign to conserve Leigham Court Road, supporting an application by modernist heritage physique Docomomo to have it listed.

“It really is one of individuals tiny gems tucked away in the backstreets,” says Rob Loader of Docomomo. “It has the ambiance of an Oxbridge school, an unexpected magical spot, with the developing conceived as a backdrop to nature. It plays video games with formality and informality, contrasting rationalist building with the vagaries of nature. There’s not significantly like it anyplace else in the nation.”

“We’re seeing an rising number of these minimal-rise housing estates threatened by nearby authorities, who are keen to maximise density on their sites,” says Henrietta Billings, conservation adviser at the Twentieth Century Society. “Leigham Court is a truly great instance of what we ought to be constructing now, with generous space specifications on what is very a tight internet site. It is so intricately made, with the 1-individual units pulled back above two-individual units to produce south-dealing with terraces, even though each detail has been lovingly thought by way of – down to the reduced window sills, so folks can nonetheless search out at the backyard from their beds.”

Officers from English Heritage have now visited the site and will be generating their own suggestions quickly. Lambeth council insists that “demolition is not on the cards,” but says it is seeking to “dispose of the internet site,” even though not just before 2018.

“It has turn out to be abundantly clear that it’s all about fulfilling targets,” says Jonathan Bartley, chair of Lambeth’s Green Get together, who efficiently fought to conserve the close by Glebe sheltered housing neighborhood last year. “It has nothing to do with taking account of the wishes of residents, the real state of the buildings, or the significance of the architecture. The council is moving towards a health-related care-primarily based model of old-age, rather than a social model, geared in the direction of putting individuals in small boxes and charging them for added companies they never require.”

“Lambeth claim to be a ‘co-operative council’, carrying out factors in partnership with residents, not undertaking things to them,” he adds. “So the potential of 269 Leigham Court Street will be the actual check of their flagship policy.”

The battle to conserve Lambeth"s modernist sheltered housing

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder